By Mary Anne Kennan

This article was first published in the special issue of Incite “Build it and they will come”. The intention was to examine how libraries and other information organisations promote and celebrate their services and the profession. If one searches on the string “Build it and they will come” in the Proquest journal database which comes to us as a part of our ALIA membership there are 84 articles in this relatively small LIS subset of the database from 1994 to the present which have the phrase in their title, text or references. The articles vary from research, to reports of services offered in particular libraries and what has worked (or not), to scholarly (and other) opinion pieces. Many of these types of publications we can use as evidence to inform our practice as information professionals for day to day decision making, developing new services, improving the quality of existing services and understanding our users. So let’s see what some of these papers say about “build[ing] it and they will come”.

There is not enough space in this short article to reprise even the small proportion of articles on this topic in this database, but what we can draw attention to, is broadly what the message seems to be: that is that it is not enough to just build a wonderful service. What the literature seems to say is accompanying the building of “it” – whatever the “it” is (a service, a digital collection, a repository, a building, a change) there needs to be a strategic approach to understanding user, and potential user, needs and their environments, communities and goals in the development of the service (e.g. Moyer& Coulon 2012; Salo 2008; Schlosser & Stamper 2012). It is not enough to think you may know what those needs are; your service is more likely to be successful if you reach out and consult, or even partner, with users and potential users (e.g. Kenney 2014; Moyer & Coulon 2012; Salo 2008; Schlosser & Stamper 2012) at all stages - service development, implementation and use.

Then of course are the other key elements in building a new service - well known and mentioned frequently in this issue - so covered only briefly here: promotion and marketing. Outreach is critical – make the new service visible. Social network, both online and in person. Leverage other media, such as the press, radio, and local bloggers (e.g. Doster 2013; Kenney 2014; Moyer & Coulon, 2013; Schlosser & Stamper 2012). In some cases, particularly involving new technology or practices, it is necessary to educate users and staff (Salo 2008). And to give the final words to Kenney (2014) “Meet people where they are – not where we want them to be”.

References

Doster, A. (2013). Friday night: library lights. American Libraries, 44(11), 30-32. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1466133420?accountid=50932

Jones, N. B., & Mahon, J. F. (2012). Nimble knowledge transfer in high velocity/turbulent environments. Journal of Knowledge Management, 16(5), 774-788. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13673271211262808

Kenney, B. (2014). The user is (still) not broken. Publishers Weekly, 261(4), 19-n/a. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1492572274?accountid=50932

Moyer, M., & Coulon, A. (2012). LIVE at your library! American Libraries, 43(11), 46-48. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1223377171?accountid=50932

Salo, D. (2008). Innkeeper at the roach motel. Library Trends, 57(2), 98-123. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/220445916?accountid=50932

Schlosser, M., & Stamper, B. (2012). Learning to share: Measuring use of a digitized collection on flickr and in the IR. Information Technology and Libraries (Online), 31(3), 85-93. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1080967094?accountid=50932

|

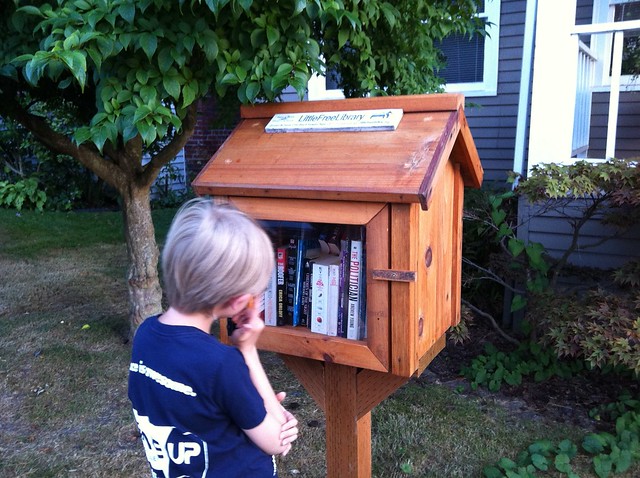

| Little library bit.ly/1pI7x06 |

There is not enough space in this short article to reprise even the small proportion of articles on this topic in this database, but what we can draw attention to, is broadly what the message seems to be: that is that it is not enough to just build a wonderful service. What the literature seems to say is accompanying the building of “it” – whatever the “it” is (a service, a digital collection, a repository, a building, a change) there needs to be a strategic approach to understanding user, and potential user, needs and their environments, communities and goals in the development of the service (e.g. Moyer& Coulon 2012; Salo 2008; Schlosser & Stamper 2012). It is not enough to think you may know what those needs are; your service is more likely to be successful if you reach out and consult, or even partner, with users and potential users (e.g. Kenney 2014; Moyer & Coulon 2012; Salo 2008; Schlosser & Stamper 2012) at all stages - service development, implementation and use.

Then of course are the other key elements in building a new service - well known and mentioned frequently in this issue - so covered only briefly here: promotion and marketing. Outreach is critical – make the new service visible. Social network, both online and in person. Leverage other media, such as the press, radio, and local bloggers (e.g. Doster 2013; Kenney 2014; Moyer & Coulon, 2013; Schlosser & Stamper 2012). In some cases, particularly involving new technology or practices, it is necessary to educate users and staff (Salo 2008). And to give the final words to Kenney (2014) “Meet people where they are – not where we want them to be”.

References

Doster, A. (2013). Friday night: library lights. American Libraries, 44(11), 30-32. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1466133420?accountid=50932

Jones, N. B., & Mahon, J. F. (2012). Nimble knowledge transfer in high velocity/turbulent environments. Journal of Knowledge Management, 16(5), 774-788. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/13673271211262808

Kenney, B. (2014). The user is (still) not broken. Publishers Weekly, 261(4), 19-n/a. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1492572274?accountid=50932

Moyer, M., & Coulon, A. (2012). LIVE at your library! American Libraries, 43(11), 46-48. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1223377171?accountid=50932

Salo, D. (2008). Innkeeper at the roach motel. Library Trends, 57(2), 98-123. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/220445916?accountid=50932

Schlosser, M., & Stamper, B. (2012). Learning to share: Measuring use of a digitized collection on flickr and in the IR. Information Technology and Libraries (Online), 31(3), 85-93. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1080967094?accountid=50932

Mary Anne Kennan is the Higher Degree by Research and Honours Coordinator and Senior Lecturer at the School of Information Studies, Charles Sturt University.